I wrote this literary criticism for LIBR 265, San José State University. It earned 10/10 points. Read the rest of this entry »

-

0 Bravos & Boos (Comments)

0 Bravos & Boos (Comments) -

Blog Post #1

http://ischoolblogs.sjsu.edu/students/basilioserna/2014/08/31/libr-200-intro/

“Hi Basilio, I’m Jordan. I like your name – I’m an opera lover and it’s the name of a character in “The Barber of Seville” and “The Marriage of Figaro.” Libraries are like a second home to me too, and I’m also interested in academic librarianship, especially in the field of music. I wish you the very best of luck!”

Blog Post #2

http://ischoolblogs.sjsu.edu/students/kimberlyhannaford/2014/09/14/blog-2-older-adults-as-an-information-community/

“What a valuable study topic! Just by casually observing libraries, I can tell that older adults are one of the most prominent information communities, and one that needs particular assistance and guidance for various reasons, not least the fact that many seniors lack technological savvy. Kudos to you for giving them the attention they need!”

Blog Post #3

http://ischoolblogs.sjsu.edu/students/acurtis2/2014/09/27/libr-200-10-blog-post-3-report-on-information-community

“Good job with your interview! I never knew much about what archivists do before. I’ll have to keep all this in mind in case I ever need to consult an archivist myself.”

Blog Post #4

http://ischoolblogs.sjsu.edu/students/acurtis2/2014/10/12/libr-200-10-blog-post-4-information-communitys-perceptions/

“Excellent interview and reflections. In hindsight, I wish I had asked my interviewees the questions that you asked, in addition to my own.”

Blog Post #5

http://ischoolblogs.sjsu.edu/students/srich/2014/10/25/libr-200-blog-5-legal-and-ethical-issues-pertaining-to-american-immigrants

“I have yet to work in a library, but I’ll keep all you’ve written here in mind, especially since I live in LA, a city with a huge immigrant population. The balance between helping patrons as best we can and maintaining the necessary legal and ethical standpoint can be a difficult one. I’m glad we have the opportunity to discuss and analyze it and hopefully learn from each other.”

Blog Post #6

http://ischoolblogs.sjsu.edu/students/colleengoos/2014/11/09/56/

“Excellent post! Your views on stereotypes and dress will be worth remembering when I enter the library work force, and I love your meme. It perfectly captures the difference the sources of knowledge that TV promotes vs. better sources of knowledge that are often overlooked.”

Blog Post #7

http://ischoolblogs.sjsu.edu/students/meanderings101/2014/11/23/yik-yak-dont-talk-back-libr200-blog7/

“Nice observations. I own a smart phone, but I’m still just getting the hang of apps and sometimes feel like a dinosaur. My old-fashioned mind would never have thought to consider apps an information source in the same sense as libraries. But for better or worse, as you said, they are!”

Book Review

http://ischoolblogs.sjsu.edu/students/acurtis2/2014/11/10/alyssa-curtis-libr-200-10-blog-book-review/

“This book sounds excellent. Increased user participation seems to be the direction that a lot of information sources are taking nowadays. I think I approve of that change, though I need to do more research on the subject. Increased user feedback and integration of the museum/library/etc into the community sounds good to me! I’m tempted to look for a copy of this book based on what you’ve written.”

-

Until I took Libr 200, I never realized the scope and complexity of the world of music librarianship. I knew I was interested in it, but I didn’t realize how many things it encompasses. But now I know all the different types of music librarianship that exist: academic, performance, HIP, etc. I know the multitude of responsibilities that a music librarian has: preserving scores and recordings, distributing them to scholars and musicians, researching period music styles to ensure that performances are “accurate,” interacting with conductors, music publishers, etc, and staying abreast of the latest technology and the community’s ever-changing information needs. I know the legal and ethical issues librarians need to grapple with and the stereotypes they need to combat. I know the type of experience and education needed for a career in the field. And I know how technology and digitization are changing not only the nature of music librarianship, but the music industry as a whole.

I realize now that if I want to be a music librarian, I’ll need much more education. As a non-musician, I’ll need to find the necessary training from people who do have instrument-playing experience. I’ll also need to decide which type of music library is the best environment for me, learn what openings are available in that category, and try to become more technologically savvy, so I can work effortlessly with the software and digital files that are becoming so important to the world of music. I’ll research courses that are specifically in music librarianship, to see where they’re offered and what the requirements are. I’ll follow all the most recent surveys of the music information-seeking community to make sure I fully understand their needs, both present and future. Music librarianship is a fascinating field, more so than I ever dreamed it would be, and I’m looking forward to exploring it more deeply.

-

The importance of modern technology in academic music libraries is clear. The music recordings in their collection, which professors and students rely on, are increasingly being stored as digital reserves rather than records or CDs. But how does digital technology matter in performance libraries? Does it help those librarians serve their information-seeking community, too?

The answer can be found in Patrick Lo’s 2014 article An Interview with Matthew Naughtin, Music Librarian at the San Francisco Ballet. This interview is effectively a follow-up to Lo’s earlier interview with the Metropolitan Opera’s chief librarian Robert Sutherland, despite being published in a different journal. It covers much the same ground as the Sutherland interview, describing a performance librarian’s responsibilities, though it outlines several factors unique to ballet librarianship and foreign to opera companies. But it also discusses a factor not emphasized by Sutherland, but which is probably universal to all performance libraries today: the benefits of digitization.

One of a performance librarian’s main jobs is to preserve sheet music, proofread it, and edit it to make sure it’s completely error-free. This is obviously a difficult task to do by hand. But with the advent of music notation software, scores can now be computer-engraved into PDF files (Lo & Naughtin, 2014, p. 153). The editing work can now be done on computer, and multiple digital copies can be made of a single error-free score.

Performance librarians also need to distribute sheet music to every musician in the company, as well as to fellow music librarians with whom they collaborate. Traditional mail is slow and not always reliable as a distribution method. Though Naughtin still uses it when he needs to, he prefers sending PDF files by e-mail (Lo & Naughtin, 2014, p. 146), and I’m sure that many other librarians agree with him. He also enthusiastically praises the San Francisco Ballet IT Department’s new website (Lo & Naughtin, 2014, p. 154), which will let musicians upload not only sheet music PDFs, but MP3 audio files onto their iPhones and iPads, so they can practice their music with both visual and audio guidance.

It’s clear from this interview that digitization is bringing ease and innovation to every subset of music librarianship. I’m sure that within a few decades, or even years, few librarians will even remember a time when digital technology wasn’t essential to their work.

References

Lo, P. & Naughtin, M. (2014). A conversation with Matthew Naughtin, music librarian at the San Francisco Ballet. Music Reference Services Quarterly, 17(3), 142-168. doi: 10.1080/10588167.2014.932677

-

The Future of Music by David Kusek and Gerd Leonhard is a must-read for any music lover who’s ever worried about the fate of his/her beloved art form. So often in recent years we’ve heard that the music industry is dying, with the collapse of the leading record stores (Tower, Virgin, etc.) and decline of CD sales cited as proof, and the phenomenon of digital distribution is blamed. But Kusek and Leonhard offer a much more optimistic viewpoint. They argue that while yes, the record industry is dying, the music industry is alive and well. The record industry, they claim, relies on an outdated top-down business model and copyright laws that chiefly benefit the record labels, not the musicians, and certainly not customers who have to pay for overpriced CDs. The music industry’s future, they argue, lies in digital distribution. Copyright laws will change, file sharing won’t be criminalized, consumers will be increasingly able to access music of their choice at little cost, and more new artists than ever will be exposed to the public and launch their careers without needing millions from a major label first. Music will become “like water; ubiquitous and free-flowing” (Kusek and Leonard, 2005, p. 3).

What these changes to the music industry will mean for music librarians, I don’t know. Music libraries will obviously rely more heavily on digital reserves, as they already increasingly do. While I doubt their collections of vinyl and CDs will ever be irrelevant (particularly since copyright issues and other factors will keep certain recordings from ever becoming available digitally), they’ll presumably become increasingly less important as the demand for digital music increases and the libraries rely ever more on computers and software. But regardless of how libraries are effected, it’s reassuring to read a counter-argument to claims that the music industry is doomed. According to this book, the industry’s format is simply changing, as systems that distribute information always change over time.

References

Kusek, D., & Leonhard, G. (2005). The future of music: Manifesto for the digital music revolution. Boston, MA: Berklee Press.

-

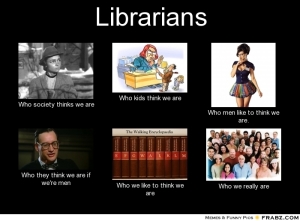

Each of the first five images I chose represents a classic stereotype about librarians: the “old maid,” the “enforcer,” the “sex object,” the nerdy, pathetic male librarian, and the “walking encyclopedia.” The last image shows information professionals as they really are: ordinary people. Men and women of all ages, ethnicities, backgrounds and personalities, who happen to have chosen a career in information.

-

In a music library, or any library for that matter, it’s essential for librarians to know exactly what patrons want and how they use the available resources. They need that knowledge to improve their services, and as Hursh and Avenarius (2012) write, “Improving services is what librarians are all about” (p. 84). But how should they acquire that knowledge? Attempts to answer that question can lead to ethical issues rearing their heads.

Privacy is always an important issue in library ethics. When conducting studies to determine patron wants and information-seeking patterns, librarians need to take utmost care to respect the participants’ privacy, which can be difficult. For example, when a music library publishes the results of a survey about patrons’ use of online reserves, the interviewees’ answers should be anonymous, with no “personally identifying information,” yet still with “enough specificity to determine whether the reserve recordings were accessed from on campus or off campus” and other important details (Phinney, 2005, p. 12). Ideally, participation in the study should also be “strictly voluntary,” with “no incentives” to make reluctant patrons participate (Phinney, 2005, p. 12). But ideal though that approach may be from an ethical standpoint, it may keep librarians from acquiring all the needed information.

A study of only a select few patrons who choose to be surveyed will offer a less complete portrait of mass information-seeking behaviors than a compulsory study of all patrons would. Furthermore, face-to-face interviews and surveys “can be misleading, because people often say one thing but do another” (Hursh & Avenarius, 2012, p. 85). Some librarians argue that an ethnographic study, combining interviews or surveys with periods of secretly observing everyday patron behavior, “results in a more complete and accurate picture” (Hursh & Avenarius, 2012 p. 85). But this presents an ethical dilemma: is it right for librarians to “spy” on patrons and record their behaviors for a published survey without their knowledge? Hursh and Avenarius (2012) have no qualms with this approach, because “no information [is] recorded that could later be used to identify specific individuals, and there [is] no manipulation of the subjects to get them to act in certain ways” (p. 90), but still, ethical concerns remain.

Librarians who conduct patron studies have a difficult balance to strike: giving maximum respect to patrons’ privacy vs. gaining the most complete and accurate study results. Ultimately the nature of the study, the needed information, and the library itself will have to determine what type of study methods should be used. Librarians will need to observe every factor at stake and determine which side of the dilemma – privacy vs. completeness – should be emphasized to give patrons maximum benefit in the long term.

References

Hursh, D. W. & Avenarius, C. B. (2013). What do patrons really do in music libraries?: an ethnographic approach to improving library services. Music Reference Service Quarterly, 16(2), 84-108. doi: 10.1080/10588167.2013.787522

Phinney, S. (2005). Can’t I just listen to that online? Music Reference Service Quarterly, 9(2), 1-33. doi: 10.1300/J116v09n02_01